Kyoto University of the arts

Honourary award ceremony

Commemorative speech

by

Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão

“Peace and Culture: The Arts in the service of Peace”.

Kyoto University of the Arts

Tokyo, Japan

23 November 2021

H.E. Yutaka Tokuyama, Chairman, Board of Directors,

H.E. Takahiro Niwa, Vice-President of the University,

H.E. Sukehiro Hasegawa, Distinguished Professor at Kyoto University,

H.E. Yasushi Akashi, Former Under-SG and SRSG of the UN for Cambodia and Yugoslavia,

Mr. Takehiro Kano, Deputy Assistant of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Mr. Tadamichi Yamamoto, Former SRSG for Afghanistan,

Mr. Naoto Hisajuma, Director-General of the Secretariat of the International Peace Cooperation,

Mr. Toshya Hoshino, Former Ambassador to the UN and Professor at Osaka University,

Distinguished Ambassadors from ‘g7+’ countries,

Distinguished Deans of Faculties and Departments from Kyoto University of the Arts,

Distinguished Guests,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Dear Students,

It is a great pleasure for me to be here at this University of the Arts to share a little of my vision on “Culture and Peace” with you, young artists.

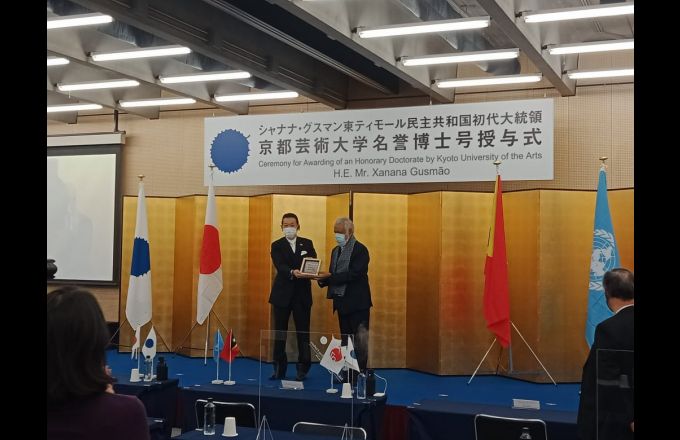

I would like to start by thanking the Kyoto University of the Arts for the academic Award it has bestowed upon me today. It is a great honour - and perhaps a source of inspiration for me to dedicate more time to painting, which is something I always loved, but which circumstances did not allow me to pursue.

Arts provide human beings with knowledge, harmony and happiness. Arts build citizenship and consolidate development. This is true for any period of history, but never truer than in the most critical times, both for individuals and for the world as a whole.

However, not everyone has the gift possessed by you, my dearest students of the Kyoto University of the Arts. Sadly, creativity is a talent that is increasingly rare and that is not nurtured enough in our societies.

Faced with many competing priorities, politicians tend to pay little attention to culture. While they may consider it a less critical sector, I believe it is just the opposite. Culture is an important structural element in any society. I say that culture and the arts should be present in the lives of everyone, from toddlers to senior citizens, and particularly those in the higher echelons of leadership.

You, the creatives, may assist humankind in achieving what it needs the most: a world of peace, tolerance, mutual respect and solidarity.

You, my dear students, have the ability to work in a context of ambivalence, contradiction, complexity and change, so common in today’s world.

You have a superpower! You are able to transform the unpleasant world around us into something beautiful and stunning, which imbues us with hope. Culture, and particularly the arts, brings people and ideas closer and can have a liberating effect.

I think that is why I went back to painting and poetry during my seven long years as a political prisoner. I went from an idealistic guerrilla fighter to an idealistic prisoner, and it was culture that helped me to endure imprisonment. While the Timorese resistance continued to fight against a dictatorial regime and an illegal occupation, I felt powerless... and the only place where I could find relief from my frustration and anguish was in the arts.

It was during this search for lost dignity and for the determination to continue fighting the powers that be of an international system, so indifferent to the Timorese suffering, that some people were kind enough to label me as a “painter and poet”.

Back then, I used to proclaim:

“(...) Cultivate love

and love Peace!

We were brothers, we are brothers

In the pain of THE STRUGGLE

We are brothers, we will be brothers

In the freedom of PEACE.”[1]

[1] “Sea of mine - poems and paintings” (1998), Xanana Gusmão

My dream of finding a world of peace did not grow dim, neither when I was inside a prison cell nor now, that I am free once more. But there are others who remain prisoners... imprisoned in lives of poverty and conflict.

Millions of men, women and children yearn for freedom. The world cannot take any more violence and misery. The world does not need more hubris, ambition and opportunism. The world needs dialogue and passions that mobilise people towards the common good.

The world needs the arts. And the world needs peace – what an enormous challenge and what a beautiful dream!

Your creativity may therefore be instrumental in establishing a world of peace, since nothing is more attractive than messages that appeal to our senses. Use that creativity to make a world of peace go viral.

Excellencies

Ladies and gentlemen

Dear Students,

Today’s world is challenged and tested every day, in a state of disorder and chaos. World leaders, as well as their agencies and multinationals, are lost amongst rambling and selfish priorities.

In all global conferences, such as the latest Climate Conference in Glasgow, world leaders come together to smile and make statements asking the poor to become even poorer, while the countries polluting the planet the most, and that have achieved a comfortable level of development, sleep peacefully, because they have banned plastic straws and drive electric cars to work.

And still, one cannot say that the Summit was a failure. Despite everything, a few steps were taken to actually protect the planet and a few commitments were strengthened. There was environmental awareness and there was dialogue and communication seeking to respond to the most serious threat looming over the future of humankind.

Even though there is still some time left before the upcoming catastrophe, there is an increasing awareness as to the urgency of climate matters.

But what about the urgency to resolve migratory crises? Thousands of men, women and children die in the Mediterranean trying to reach Europe, or in the Indian and the Pacific trying to reach safe havens. At the US/Mexico border, people despair in overcrowded shelters, living in miserable conditions. But the height of cynicism is the Poland/Belarus border today, where thousands of people freeze at the doors of Europe.

What cultural legacy is this… that creates monsters unable to respect human life? These are human beings – like you and me – running from war, hunger and political persecution. How can they be used as political weapons?

And even understanding the pressure placed upon destination countries, how can we let people living in inhumane conditions slip from our minds for hours, days, months or even years?

World leaders insist on remaining steadfast in their perceptions. Mistrust and uncertainty undermine relations between people, between people and States, and even between States. Meanwhile, new areas of conflict arise throughout the world.

There is fear that refugees will bring their background of suffering and violence to recipient countries; that they will alienate rights and that they will take jobs, education, health care and even principles and values from the citizens of those countries. Still, our powerlessness and passiveness on such vital matters make us all more inhumane.

While the supremacy of the strongest and the richest prevails, we will see the growth of the most fragile and the poorest. While the world continues to harbour feelings of ethnocentrism, racism and xenophobia, as well as other types of prejudice and fundamentalism, stability will be under threat everywhere.

Still, the International Community insists on ignoring the root causes of problems. Instead, it continues to hold that the endless wave of refugees is only a by-product of wars, which is to say the absence of peace in the countries of origin.

We are constantly reminded that there is no oasis of peace and security in places where there is misery, war and conflict. And yet the West continues not to acknowledge and face the consequences of its own policies, preferring instead to continue stoking the fires of mistrust and uncertainty in the future – your future!

You will recall that over these nearly two years of Covid-19 pandemic, there were many who wanted to believe that this was an unique opportunity for building a better world. There was much talk about cooperation and scientific breakthroughs. There was talk about solidarity inside and across borders – that once a vaccine was created no one should be left behind.

Unfortunately, vaccination rates in Africa are extremely low. This is a flagrant example of the failure of international solidarity. It is a failure, because we continue to lack the capacity to assist those who need it the most. It is also a failure, because our selfishness makes us blind to the risks of a new public health crisis.

It turns out that the pandemic did not bring the cure for all the ills of humankind. Neither did the climate emergency, nor watching the suffering of thousands of people, through the media to which we all have access. It seems, there is no ill in the world that is able to build sound and uninterested international cooperation that puts people at the centre of every agenda.

On the contrary, international solidarity in action, quickly turns into forgetfulness in action. Tragedies keep occurring one after the other, while the number of victims keeps piling up.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Dear Students,

Looking at history, one cannot forget the interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, where wars were started in the name of democracy and human rights – wars that are yet to end. We cannot forget the movements of the “Arab Spring”, which challenged dictatorial regimes, only to become a “Long Winter”.

We cannot forget South Sudan, Somalia, the Central African Republic, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Yemen and so many other countries. Africa is wounded from the inside and despised from the outside.

The conflict between Palestine and Israel, one of the longest in history… are we really to believe, that divides are so deep as to leave no room for understanding?

A couple of months ago there was much talk about the Afghan tragedy. Much was said about the Afghan women and girls who, after having lost so much, were now about to be deprived of their most precious asset: hope.

After nearly two decades of an intervention that failed to produce lasting results, the US called “mission accomplished” in Kabul and departed, leaving behind a country in chaos. Almost two decades preaching democracy and human rights, only to end up with more deaths and a terrifying void.

Although since 6 of May 2010 Afghanistan did not host any international events, on 23-24 March 2016, ‘g7+’ held a ministerial meeting in Kabul.

At that time, I met with an old Dignitary, newly appointed by the President of the Republic of Afghanistan, who had responsibility for dialogue and reconciliation within the country. He confessed that the problem in Afghanistan was not only with the Taliban, but also with the drug trade as well as with Pakistan in the border regions.

This all reminds us that the presence of international forces was not the most appropriate approach, which has become even more apparent with the problems, associated with departure of international forces from Afghanistan. And that is why, we need to consider problems more effectively and comprehensively.

The only possibility that seems feasible is to re-establish the economy in Afghanistan. This requires considerable engagement with the Taliban regime. The intra-Afghan peace process must be based around principles of ownership and inclusion. The international community must continue to support Afghanistan and to not give up on its people.

And in Afghanistan, the problem goes beyond the relationship with the Taliban. There are many other causes and factors that, sometimes, escape the Western lens.

The regional actors must be constructive and impartial. Also, they must once and for all decide what matters most: human rights or realpolitik; business opportunities or geostrategic influence.

The International Community must tread lightly. In addition to understanding the transition of power well, it must accept that the paradigm that failed over the last two decades must now be changed. The universality of the Western regimes is not in tune with the realities of each country and each people.

This is why it is time to revise engagement paradigms, encapsulated into civilising missions that seek to implement exotic concepts that never had roots in the target countries.

And yet, this is not merely a matter of human rights and freedom. The Taliban government inherited a miserable country without drinkable water, sufficient food or the most basic conditions for people to survive. This happens in many places of the world, not just in the Middle East.

How much longer will democracy continue to be a mirage in Myanmar? Tensions in this country have been high for decades, and are made worse by the Rohingya issue, which is strongly condemned by Western countries.

The Rohingya minority is not the only problem in Myanmar. The Burmese are also subject to the pressure of alienation of their cultural and identity.

In the case of Myanmar, the situation with the Rohingya and the condemnation by Western countries must also be considered. It is true that Rohingya Muslims are among the most persecuted minorities in the world. I went to Myanmar, more than 10 years ago, to seek to understand the situation. I came to the conclusion that the issue cannot be seen through a single lens. There were militias, which did not even represent the Rohingya population, demanding a “democratic Muslim state” within a nation that already exists.

This was creating tensions in Myanmar, including about national identity and culture, as well as causing border security issues with Bangladesh with the influx of refugees.

It is known that wherever there is conflict, misery and violence, there are people who need to flee. I refuse to accept the International Community’s selfishness on this matter. Timor-Leste has had also thousands of refugees abroad, during the war, and, in the beginning of our independence, we have had many internally displaced persons. Would anyone, in their right mind, abandon their home and all their belongings, unless they are in a desperate situation?

From the people in the detention centres in Australia, to the Mexico-US border and those trying to enter Europe, they are all human beings – like me and you – desperately in search of peace.

I understand that the latitude and longitude of these crises is such, that they do not cause us to lose sleep over them. Still, let us not fool ourselves. We are all responsible for our passiveness in preventing crises. Indeed, we are complicit, whether due to impotence or indifference, with the electing leaders that promote war and conflict.

More recently, at the Polish border of the EU with Belarus, refugees have become pawns in the hands of political interests. This is complete disregard for human life!

Let us please take notice to see whether geo-strategic influence and “realpolitik” will once again prevail. And let us see whether those, who publicly talked about the duty of solidarity, will not be the first ones to close borders on a problem that is just starting.

I believe it is essential to have greater international cooperation, well beyond the global public health crisis. Inequalities across and inside our borders are appalling. We must eliminate the disparities in the access to knowledge, education, modern technologies and tools for human development, which became even clearer during the pandemic.

If we truly want to build a world of peace, then we must focus on capacity-building.

This is the time to revise engagement paradigms, so that they contribute to peace. This is the time to act pre-emptively, together, in order to resolve crises that affect us all.

No one can do everything alone and no one knows everything about everything. Some know what it is to live in inequality, while others know what is like to theorise about it. We need to build a bridge between these two groups.

We must have greater representation and more perspectives, from all corners of the globe, when discussing issues and challenges, so that solutions are indeed global.

This can only be achieved by bringing fragile States closer to the International Community and its agencies.

Trough ‘g7+’, I also visited the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Haiti and others. There, I met with the leaders of State and of Civil Society. The conclusion was always the same: there are always different perspectives on the same problem, and regardless of the perspective, one cannot look at a problem through only one lens.

While only the vision of the strongest prevails, development will never be for everyone. Thus, we must return to multilateralism.

Last September, the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, launched a document titled “Our Common Agenda”, focusing on crisis prevention instead of “business as usual”, where we pay the price for the inability to foresee crises and to plan responses in good time.

I should add that this price is always steeper for those, who are actually living through the crises. I believe that, a common agenda that is centred on the dignity of the human person, is a good starting point, provided that it is taken seriously.

It is undeniable that the UN and the Security Council need to be reformed, in order to be more efficient and effective. The permanent members of the Security Council should favour international diplomacy over confrontation. The UN is still the key arena for multilateralism, and it can be improved with everyone’s contribution.

The most dangerous threats in any internal crisis are arms races and geopolitical divides, which may slide into armed violence.

In previous American administrations, leaders met in the morning to talk about peace and in the evening they signed arms deals. I hoped the new administration would be more consistent in honouring its electoral promises, especially with regard to limiting arms sales to countries whose military offensives cause atrocities.

But, unfortunately, the reality is very different and we must praise a group of US Senators who, just last Thursday, expressed their opposition to the Biden administration’s first major arms sales to Saudi Arabia, for its involvement in the war in Yemen, a conflict considered one of the world’s worst humanitarian disaster.

Most conflicts in fragile countries are the result of hegemonic policies by powerful nations. Fragile countries are often used as battlefields in which other parties wage their wars.

Excellencies

Ladies and Gentlemen

Dear Students,

Without reducing instability and economic inequalities within countries and between countries, any global sustainable development plan, like the one featured over the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), will be merely a pipe dream.

We want to believe in the commitments made in the 2030 Agenda, in which the UN elected peace as a cornerstone, acknowledging its importance to global development.

And yet, in the countdown to this common agenda goal, over 1.5 billion people live in countries where development is compromised by fragility and violence. I know from experience, in my country, that “without peace there is no development” and that “without development there is no peace”.

It is urgent that we improve multilateral diplomacy and that we adopt preventive diplomacy, so that events do not escalate into conflicts, particularly since the reaction time of the international community is slower than the speed at which events unfold. A more fruitful relationship between the International Community and its agencies on one side, and fragile and in-conflict or post-conflict countries on the other, might correct this time lapse.

Our experiences, in the struggle for liberation and in breaking away from a situation of instability and fragility, led us to want to share experiences on reconciliation, Statebuilding and Peacebuilding. Thus, in 2010, we established a group, the ‘g7+’, which shares the same challenges and ambitions.

This group is an intergovernmental Organisation that brings together 20 conflict-affected countries from Africa, Asia, the Pacific and the Caribbean, which are transitioning from conflict to resilience.

Our member States have very different backgrounds and geographic, historical, cultural and political characteristics. Still, they all have people suffering and dreaming of a world of peace.

Amongst our various goals, we want to:

- Share experiences on reconciliation and peace, through the “Fragile to Fragile (F2F) Cooperation” program;

- Take part in the global discussion on sustainable development in fragile States and contribute to a new world order, where States, like ours, are represented and where our voice is heard, particularly when discussions are about us.

- Strengthen internal resilience and the relationship with international partners. In addition to civil war, terrorism, natural disasters, hunger, disease and despair, our people also have to deal with foreign condescension and interference. And yet, we hold on to the hope of a better tomorrow – a brighter future for the next generations.

- Build our States according to the best practices, while respecting our realities and idiosyncrasies. We are aware that we need to invest in consolidating our agencies, so as to respond to the needs of our people.

- Promote country-led dialogue, both internally and with foreign partners. This requires political leaders to set aside all their antagonisms and to fight the ‘status quo’ of internal dependency. We are the ones most responsible for our fate and it is up to us to contribute the most to any solution. As such, it is concluded that peace can never be imposed by mechanisms that are alien to us. Instead, it must be an internal process that engages every agent in our society, towards the collective interest.

Dear students,

The ‘g7+’ is but a meeting of cultures from countries that are already multicultural, in view of their common history of mostly European colonisation.

And while our meetings are almost always difficult, because we are speaking about our own past or present hardships, they still have their beauty. Indeed, when we open our hearts to talk about stories of hatred towards others or towards ourselves, stories of intolerance and despair, stories of tiredness in words and actions… we become closer to those others.

We understand the beauty of other people. The beauty of other practices, cultures and arts. We understand their weaknesses and expectations. It becomes a process of reconciliation, something that is so direly needed in many parts of the world.

That, which is a condition of fragility, may be transformed into trust and may create space for dialogue and mutual respect. And where there is dialogue and respect, there are conditions for negotiating and resolving divergences and for moving forward with the ambition of achieving peace and sustainable development.

Your Excellencies

Ladies and gentlemen,

Dear Students,

It is time to cultivate a culture of interdependence, which is something that we already have. It is time to return to multilateralism, which does not threaten the sovereignty of different countries. In fact, it does just the opposite.

The key problem today is the complete lack of trust between people, and particularly between people and the agencies that lead them, both at national and international level. This mistrust and disbelief in agencies and their policies are detrimental to the creation of conditions for building peace or even combating the global pandemic.

People do not look after one another. Societies do not look after one another. This leads to global despair, instead of consolidating a culture of general benevolence.

It is, when our problems are not met with a response, that our actions become increasingly individualised, in accordance with our cultural roots. Hence, the importance of knowing and respecting the culture of each individual and each society. These cultural roots must also be taken into account, when it comes to climate matters.

If we are indeed serious about mitigating climate change then, over a period of little more than three decades, we will have to change our culture all over the world. This goes, from the manner in which we see our subsistence or market economies to the manner in which we eat, dress, travel and even warm ourselves.

This is an enormous challenge. It is a collective challenge. However, those that contributed the most to this situation of environmental fragility must also be the ones to take the first step forward, respecting the needs and situation of others in the world.

We do not want to leave anyone behind. Still, due to inequalities built over hundreds of years, there are countries that should take the lead in this fight and carry most of the weight. This is the only way, we will be able to save humankind.

The reason why I am telling you about all of this, is that art, in its various shapes, is also a way of intervention and demonstration. Works of art may lead us to expose, question and even change various issues in our daily lives, which may address both, individual or global concerns.

You know this better than anyone. You know that while art may be contemplative, it is also often expositive or provocative.

Art awakes and shakes consciousness to different realities, and can thus cause positive ruptures in attitudes, behaviours and systems that need to be changed.

Dear students,

In addition to breath-taking beauty, my half-island of Timor-Leste has magnificent cultural wealth. With a strong connection to nature and our ancestors, but also with the fusion of several ethnicities, cultures and civilisations, we can say that we have the perfect raw materials for a world of art.

Another key aspect of our wealth is our youth, which represents over half of our population. Many of our young people are hugely creative and talented. Sadly, most lack access to opportunities to develop their abilities.

Thus, I say that all young people, living in free and democratic societies today, cannot forget those who are yet to attain those rights. I urge you not to forget those young people, all over the world, who possibly have talents like yours, but who lack the opportunity to explore and develop those talents.

As such, I would like to appreciate and thank the Kyoto University of the Arts for its willingness of establishing a partnership with Timor-Leste, in order to enable Timorese young people to achieve their potential. In view of this, we are trying to develop this partnership with one of our Art Association in Timor-Leste, named ‘Arte Moris’, meaning ‘Living Arts’, that will be very fortunate to cooperate and work with Kyoto University of the Arts.

We must work together to create a new civilisation moved by artistic culture and a philosophy, based on constant love for nature and humankind. Most importantly, let us not continue responding to hatred with more hatred. Let us, instead, respond with knowledge and art.

As the great Mahatma Gandhi once said: “The art of living is about making life a work of art”.

It is here, at this University, that your work begins. May that work – all of your works – have a foundation of peace!

Thank you very much.

Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão